Kid Quixotes

By Stephen Haff

The Traveling Serialized Adventures of Kid Quixote began at Still Waters in a Storm, my one-room schoolhouse for Spanish-speaking refugee children in Bushwick, Brooklyn, early in the fall of 2016, in the school’s ninth year and just two months before an election that would release a plague of fear among vulnerable people, humans in need of asylum and a second chance.

We started by translating the novel collectively, by speaking and writing, from Spanish to English, a process that continues today, six years later. (Throughout the COVID pandemic, classes have been held on Zoom, because we lost our home.)

In the early days, as the translating progressed, we decided to adapt our English version, combined with the Spanish original, as a series of bilingual, musical “Adventure Plays,” writing dialogue and song lyrics as a group, reimagining the story of a delusional old man in Spain of the early 1600s as the story of a group of Spanish-speaking immigrant children living in Brooklyn today.

The families of Still Waters left their native soil for the promise of prosperity and peace, only to run into the hard reality of the Brooklyn barrio, just as Quixote leaves his village in order to live out his fantasy of heroism and discovers that the road can be hostile to dreams. His persistence despite the wide and heavy obstacles in his path runs parallel to the undeniable determination of these families, the parents who risked everything to come to this country, and now parallel to their children, who are remaking classic Spanish literature as a bilingual vessel for their own stories and the stories of their people, and traveling together in defiance of biases.

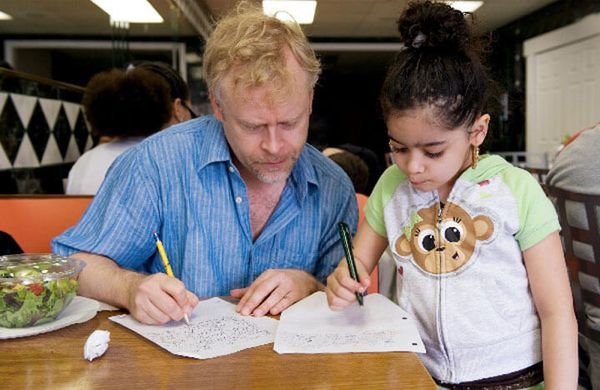

At Still Waters in a Storm, the day after the 2016 United States federal election, about a dozen of my students and I sat around our table, ready to continue our translation of el Quijote. The surface was stacked with copies of the novel in Spanish, Spanish-English dictionaries, a Latin dictionary, an etymological dictionary of English, books of synonyms in Spanish and in English, and a big coffee cup full of sharpened pencils.

But we couldn’t begin, because no one could speak. The silence was alive and monstrous. Goliath had been chosen ruler by riding a wave of racist hatred against immigrants, a fire that burns but gives no light. We use the names “Goliath “and “ruler” to remind us that such horrors have risen before, and to seek solace and resolve in the patterns of myth and history. Giants have come and gone.

In class we spoke about the very real danger the children face even now—a flyer on the wall from the Legal Aid Society said “DON’T OPEN THE DOOR! NO ABRE LA PUERTA!”—the threat of separation from their parents. We talked about the “Cold Room,” where ICE agents confine refugees, a room held at a very low temperature, and the asylum-seekers are fed frozen peanut butter sandwiches.

“What can we do?” asked seven-year-old Sarah, who would eventually go on to play the role of Kid Quixote. She’s hugging the book in her arms, as she will on stage, using it as a weapon, a pillow, a lifeboat, and a shield.

“Do you remember what you said in September?” I asked her. “When I gave you your copy of Don Quixote and I told you that we were going to translate the book?”

“I said, ‘That’s impossible. That book is too big and heavy.’”

“That’s what we do,” I said. “We do what seems impossible.”

“Why impossible?”

“We’re practicing slaying the giant, destroying the idea of impossible, so we know that when the time comes, we can bring down any Goliath.”

“With a book?!” she asked in baffled disbelief.

Eight-year-old Percy said, “We could hit him on the head with the book and knock him out!” Everyone laughed.

“Why did you choose this book?” asked Sarah.

“I chose this book for us,” I said, “because it’s our story. The crazy old man could be me, trying to help people, but he’s also you: he has the heart of a kid and he believes in what his imagination shows him, like kids do. He keeps getting beaten and knocked down, but he also keeps standing back up. That’s you and your families. You never give up.”

After class one day, little Sarah was sitting and drawing with her pencil, inside her copy of Don Quixote. A child who lives on the margins of society was making her own story in the margins of literature. I asked her if I could see what she had drawn.

“Are those doors?” I asked.

“Yes, the desert is full of doors,” she answered.

“Doors to what?”

“Doors to nothing.”

“Standing on the sand?”

“Yes.”

“Why,” I asked, “are there doors in the desert?”

“They are traps. You open the door and the Ice People grab you from below. They pull you down into their underworld.”

“Why do they live below the desert?”

“Otherwise, they would melt. Their world is a refrigerator, a giant refrigerator as big as the desert, under the desert. That’s where they keep the children.”

I pointed to a large rectangle. “Is this the refrigerator?”

“Yes.”

There was silence.

“I went there,” she told me.

“You went to the giant refrigerator?”

“Yes.”

“When?”

“Last night.”

“How?”

“I can go places when I pray.”

“How does that work?”

“I light a candle for la Virgen de Guadalupe, I go on my knees and I ask her, ‘Thanks for giving us food and classes to learn stuff, because in the future it’s going to be tough and people might try to conquer our world and we need to be ready. And please let my mommy stay with me. And I also want to be young, even when I’m old, please.’ Then I say, ‘I pray to go somewhere,’ and I go. I went to Bethlehem and saw the baby named Jesus in a barn. I also shrank myself and talked to insects. Last night Guadalupe let me visit the kids in the giant refrigerator under the desert.”

“Wow! What happened?”

Her mother arrived at the classroom door.

“I’ll tell you tomorrow,” said Sarah, and waved good-bye.

This girl was using her imagination to synthesize what was happening to her people and what was happening in Don Quixote’s imaginary world, and reimagine the partnership as a story that belongs to her.

Now, at the age of 13, on Zoom, as another giant threatens, Sarah still hugs the book to her body.

* Images Courtesy of www.stillwatersinastorm.org